Something I have …

How identity worked in the pre-computer age.

Few of us growing up in the developed world had any choice in the matter. When I was born my parents were legally required to register my birth for which they received a paper birth certificate; a verified credential which, even today, I am occasionally required to produce.

Since then, like most other people in the UK, I have become an avid collector of verified credentials that either enabled me to claim the benefits to which I was entitled or take on the responsibilities they bestow. Registering with the local doctor allowed my parents and I to use the NHS and the issue of a National Insurance number kick started my contribution towards the cost of the welfare state. In 1975 the Met Police confirmed me in the office of Constable and gave me a warrant card which came with the power of arrest; a really powerful credential that acted as both a proof of identity and authority for me to take certain legal actions. On receiving my first pay cheque I opened a bank account and the cheque book I received was another valuable and frequently used credential. Debit cards, credit cards, driving licence, marriage certificates, mortgage certificates, loan agreements, credit rating, insurance certificates, passport, degree certificate, professional qualifications and memberships all followed over the next 45 years. I still have most of these original documents, locked away in a filing cabinet in my office just in case I need to produce them some day.

Occasionally I need to carry some of these credentials so that they are immediately available for inspection; international travel and hiring a car are impossible without a passport and driving licence respectively. Knowing that I will need to present them I carry them with me, either on my person, or in my wallet.

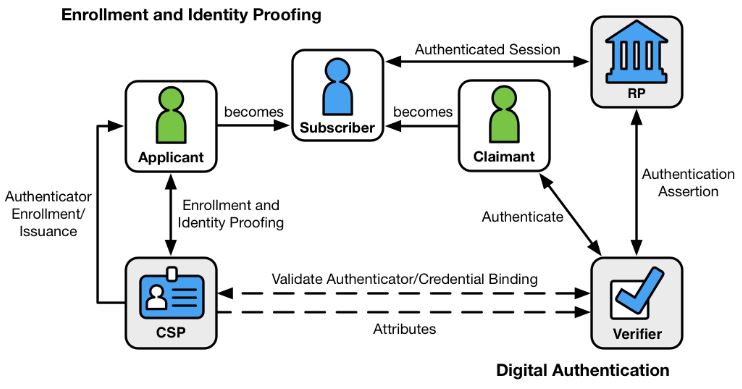

The issuing process for each of my credentials had a number of common factors – I needed to engage with a third party issuer and both parties understood the nature and reason for the transaction, on each occasion I needed to assert my identity to a standard acceptable by the other party and finally I needed to back up that assertion with acceptable documentary proof.

During those, sometimes lengthy engagements, both parties trusted the physical modes of communication, whether they be phone calls, face to face meetings, snail mail, registered post for valuable items or simply the physical exchange of signed and witnessed documents.

None of these transactions could not have happened as they did without there being a prevailing sense of TRUST between all parties. In the pre-computer era impersonation, fraud, forgery, false accounting, misrepresentation, disguise and scamming were all pretty hard to get away without specialist skills, knowledge and native cunning. Besides these, the likelihood of capture and threat of a custodial sentence deterred all but the most adventurous, or desperate.

These important physical credentials are a necessary, and in some cases legal, manifestation of my identity; they do not alone amount to my identity as a person. They are perhaps best seen as tools to enable and support my interaction with the various authorities that make up the nation state.

Before computers, issuing authorities had a clear, settled and documented step-by-step manual process for dealing with applications, employing the right number of people to make the process work but there was little or no sense of urgency.

The advent of computerisation brought opportunities to cut costs and improve the services delivered but the automation of ‘something I have‘ has not been without difficulties. Early attempts to computerise the credential issuing business led to incompatible systems running bespoke processes with first generation operating systems hosted on expensive mainframes provided by a handful of approved suppliers.

I would argue that it is only now with the introduction of the Internet, Cloud computing, ubiquitous encryption and various cross-industry working groups that the true benefits of a computerised ‘something I have‘ can be realised

Something I know …

With the rapid expansion of the Internet without an identity layer, web organisations were forced to authenticate users by the only means available to them at the time – username and password. This method of authentication is now the norm but it is a paradigm that has been completely undermined by our inability to manage these credentials securely in the real world. Don’t just take my word for it, look at the guidance produced by the UK’s National Cyber Crime Centre and the writings of Bruce Schneier on the subject.

To address the failings of username and password authentication we are now being forced down the route of the multi-factor authentication. MFA comes under the category of ‘something I know‘ because for a few seconds I need to know a one time passcode sent to me by an out of band channel (usually SMS) before entering it into the browser. This deeply inconvenient and time consuming authentication method treats only the symptoms of the identity-free Internet, not the causes of it.

There are other attributes of my identity that come under the heading of ‘something I know’. I know the dates that are important to me, my favourite teacher and I also know the answer to the ubiquitous mother’s maiden name question. The most significant problem with using these attributes to authenticate my digital identity is that its entirely possible that with a little bit of research a diligent social engineer may be able to discover all of this information and use it to impersonate me.

Something I am …

Should I die without identification on me and without my mobile phone the police have a number of biometric methods available to them to identify me – fingerprints, DNA and dental records are the most commonly used. In my case, I had my dabs taken when I joined the police service and have also recently had some very expensive dental treatment; these are clearly verified credentials that uniquely identify me.

The fundamental concept underpinning the Who.Me? experiment is the conclusion arrived at by Sariyar & Schlunder in their 2016 paper:

- Information storage – How secure is the Personal Online Datastore (POD) in which I will store my biometric data? How will the POD integrate with my digital wallet so that these verified credentials can be made available securely?

- Information exposure – What information is appended to the ledger and how do I ensure that my biometric data is not exposed?

- Proportionality – What control do I have over my data being released, how can I ensure only the correct and appropriate information is disclosed?

- Information format – What is the format of these biometric files and how can a limited and constrained amount of information be released?