In order to answer that question we need to look a little more deeply at the various terms that make up the definition of Decentralized Identity.

“A globally unique persistent identifier that does not require a centralized registration authority and is often generated and/or registered cryptographically.“

“Globally”

The GAIN proposal seeks to create a global community of trusted Identity Providers that will work together to implement an comprehensive identity overlay to the Internet. By founding the GAIN identity community on the existing global finance and payments ecosystem a solid and reliable basis for identity validation and verification is established.

Given that banks and international financial institutions have global reach, already operate a secure system (international payments) and are required to comply with worldwide Anti Money Laundering legislation, it is clear that they already possess many of the required building blocks for an interoperable international identity ecosystem.

As it expands, GAIN will increase decentralization by recruiting other international and national organisations that currently have a role as Identity Providers – internet, mobile and health service providers, universities, professional bodies, employers of all sorts and online shopping, to mention just a few. Last but not least, GAIN’s security profile is capable of providing sufficient assurance to enable governmental service providers to join, should they so wish.

“Unique”

In our daily life we are completely dependent on unique identifiers in a variety of different contexts – telephone numbers, email addresses, passport numbers, National Insurance Number, driving licence number, employee number, product serial numbers, web page locators, username and password etc. Each of these identifiers needs to be unique within its’ own context so that, for example, my phone number cannot be allocated to anyone else but the same digits in the same order could actually be the serial number for a piece of equipment I own.

Currently, all identifiers are issued by ‘someone else’ and none are currently under my control; the identifiers can expire, be revoked or compromised, as was the case of my username and password being made available toscammersfollowingthe2012 security breach at LinkedIn.

The use of existing standards, protocols and APIs alongside improvements in encryption techniques now means it is possible to cryptographically prove the ‘uniqueness’ and ‘ownership’ of an identifier.

“Persistent identifier”

A decentralized identifier not only needs to be valid and available throughout an individual’s lifespan, but it also needs to remain valid and resolvable after their death.

In many ways this is similar to the current banking requirement for account and transaction audit, however, in the future, a similar level of audit will be required for livestock, land, companies, devices and web resources, in fact anything else that needs to be identifiable long after death, upgrade or replacement.

“Does not require a centralized registration authority”

Following the success of corporate Single Sign On, federated identity started to catch on in the consumer Internet, where it led to the introduction of ‘social’ login buttons on consumer-facing websites, such as those below.

Source: Self-Sovereign Identity 2021

Each of these service providers was, effectively, operating as self-appointed Identity Providers with the capability of verifying the identities of individual account holders. For a number of reasons ‘social’ logins have, perhaps fortunately, failed to provide the Internet’s missing identity layer:

- There isn’t one IDP that works with all sites, services, and apps, so users need accounts with multiple IDPs.

- Because they need to serve so many different sites, IDPs must employ “lowest common denominator” security and privacy policies.

- Many users—and many sites—are uncomfortable with having a “man in the middle” of all their relationships that is capable of correlating a user’s login activity across multiple sites.

- Large IDPs represent some of the biggest honeypots for cybercrime.

- IDP accounts are no more portable than centralized identity accounts. If you leave an IDP like Google, Facebook or Twitter, all those account logins are lost.

- Lastly, due to security and privacy concerns, IDPs are not in a position to help us securely share some of our most valuable personal data, e.g., passports, government identifiers, health data, financial data, etc.

“Generated and/or registered cryptographically.”

The DID standard requires the identifier be capable of cryptographically authenticating the DID Controller, who may well be, but not necessarily is, the subject of the DID. Cryptographic authentication enables an identity holder to prove who they are by demonstrating they have control of the private key bound to the identifier. Such a requirement is fulfilled by the implementation of a global decentralized public key infrastructure (DPKI), which has significant security and privacy benefits for the Internet, as a whole.

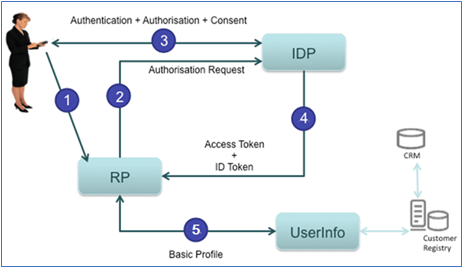

Initially the GAIN Proof of Concept, will make use of the OpenID Connect (OIDC) protocol that relies on transport layer encryption but does not, in or of itself, enable cryptographic verification of any identity information obtained by a Relying Party (RP). Further posts will explore the integration between OIDC and DID to further improve cryptographic authentication and verification.

Source developer.orange.com